The Lod You Might Not See: Your Local Neighborhood Cult

- Adam Fogelman Chanes

- Jan 13, 2021

- 5 min read

This week's blog post is written by Adam, a Yahel fellow living in Lod.

I live on the corner of Einstein Street and Shlomo HaMelekh Street in Lod, in one of the three apartments of the Yahel fellowship’s Lod cohort. If you were leave my apartment, turn the corner, roam around within the immediate neighborhood and beyond, you will notice big, daunting signs everywhere, black, bold Hebrew letters on a white backdrop:

“Fellow Jews!

Do not let This World deceive you!

Only God, His Name be Blessed!

Only the Holy Torah!”

(You might see these alongside the less common “חיים מאושרים בלי אינטרנט וסרטים,” “A happy life is one without internet and films,” or a personal favorite of mine: “אי אפשר לברוח מהקדוש ברוך הוא אבל תמיד אפשר לברוח אליו!” “You cannot run from the Holy Blessed One (God), but you can always run to Him!”

These signs belong to members of the Heichal HaKodesh community, one of countless, diverse Breslov Hasidic communities. The community in Lod, constituting mostly Haredi ba‘alei t’shuva, people seeking faith and community who became religious later in life, is considered a cult by many including the Israel Police. Heichal HaKodesh of Lod is headed by Rabbi Netanel Deri, a charismatic 39 year old leader, father to 14 children, and notorious proponent of early-adolescent and teen marriages. On Friday Nov. 11, 2020, Rabbi Deri was arrested on charges of sexual assault against minors, students of his who reported first to their parents and then the police on the horrific abuse they suffered at the hands of their rabbi and community leader.

Living in a neighborhood with a conspicuous cult presence is certainly unnerving. Even more disheartening for me personally is to witness the perversion, disarray, and immense suffering of a community of Breslovers, namely, those who follow the unspeakably, burningly profound, holy Hasidic Master Rebbe Nahman of Breslov (1772-1810), with whom I and many of my peers intensely identify in our spiritual paths. His influence on my life is still growing, pronounced by his everlasting, continuously relevant flame illuminating the corridors, doorways, and rooms of Jewish worship, meditation, breath-work, uncompromisingly virtuosic sagacity in mysticism, the knowledge that lies beyond that knowledge, and therapeutic care. The hallmark of the “Torah” (the teachings) of Rebbe Nahman is hitbodedut: go out into nature, take a seat, dwell in the brokenness of life and this world, the places at which all comforts of sense and rationality reach their breaking point, and simply speak to God as to a friend, spill out your cares before the Holy One—specifically in that place of darkness and hopelessness beyond all that is rational or ideal is where one merges with the Light, sublimates into the Sublime.

The newly revealed truth of Lod’s Heichal HaKodesh is painful for me because their rebbe is my rebbe. I make no claim that Breslov Hasidism was ever a liberal, humanistic movement. But the enlightened illumination and deep grip on the human soul that Rebbe Nahman embodies, against all odds and afflictions, feels to me crushed and shattered by the turn in Lod’s community towards populist extremism; forced distance from this-worldliness, a world specifically in which the tzadiq urged we find Divinity; and most disturbingly, manifold categories of violence and abuse turned inwardly towards the community’s most vulnerable, but experienced in one way or another by all who surrender to Deri’s will, wishing simply remain within, to maintain their sense of belonging in their community and unifying with God.

And within that suffering, far beyond my personal discomfort and dissonance with this manifestation of Breslov, I have no doubt that the hitbodedut cries of Lod’s Heichal HaKodesh Hasidim—matching or perhaps dwarfing the cries from the anonymous interviewees (links below)—might be heard in the depth of the forest. I imagine Deri’s disciples spilling their anguish before the Eternal, unable to fathom the dark world of lies in which the leader that brought them to God, Rebbe Nahman, and hitbodedut in the first place abused their children in the process, scarring them and their families for life.

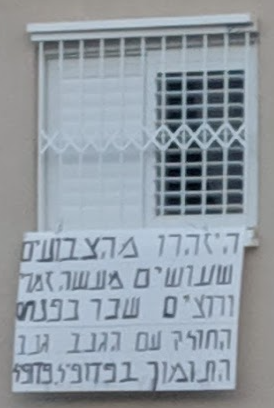

A glimmer of light, however, can be extracted from this tale of overwhelming darkness: unlike similar stories of cult leaders, including those affiliated with Breslov Hasidism, where the vast majority of cult members blindly and even violently defend their charismatic, criminal leaders, Lod’s Heichal HaKodesh community includes numerous vocal members who are actively exposing and protesting the rabbi’s misdeeds and his cult-like wielding of authority (and whose outcry may herald the seedlings of a dissenting faction and communal split). By declaring mostly anonymously (see below my photographs of anti-Deri window signs that may represent a notable exception) that nothing is holy about this rabbi, these community members are taking an immense social and perhaps physical risk, considering that communal discipline is enforced by Deri’s loyal strongmen, and that Deri himself issued subtle threats to those who might dare expose him. Beyond the rabbi’s own threats is the much less subtle threat from within the community known as a din mosseir, a religious injunction to act violently and perhaps even lethally against those who may snitch.

Rebbe Nahman, may his merit protect us from all the evils mentioned in this article, teaches in Liqutei MoHaRa"N Book II, #67 that when you behold an axis of holiness, a center of intense energy, a nucleus that gathers into itself all of the wondrous, complex, and severe qualities of the human experience—at that moment, your eyes are opened, summoned to examine the self, to see God’s world, and to cultivate awareness of the shared attributes of self and world. The city of Lod has been that nucleus of intensity for me, that rebbe, the teacher that opens my eyes to pay deep attention to the world around me, to my social, economic, and political context, to the simultaneous expressions of grief and joy in my neighborhood, my home, and myself.

This account is but one detail of my newfound social awareness, my hiddush (novel rejuvenation) in attentiveness, a trait learned as much from an environment or a breath of fresh air or an ineffable point of energy as it might be instilled by a book, professor, or activist. The learning experience that is to pay attention makes me wonder about the nuances I did not notice in past places of residence, and gives me hope in the future potential for change that might lie in the act of noticing.

(Signs protesting Rabbi Deri hung in windows directly across from the Heichal HaKodesh building, using Biblical allusions to condemn its leader, such as “Be cautioned against the hypocrites who do the acts of Zimri and desire the reward of Phinehas” (Numbers, 25), and, “‘There is no safety… for the wicked” (Isaiah 48:22). They also equate Deri with other notorious Israeli cult leaders known for sexual abuse, such as Goel Ratzon.)

Comments